|

|

|

|

|

|

|

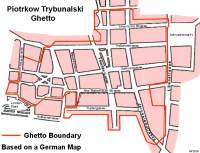

| Ghetto Map |

|

| Ghettos |

|

| Aerial Photo |

|

| Market Place |

After some initial bombing and shelling, Piotrkow was occupied on 5 September 1939. The persecution of the Jewish population began immediately. Men were seized in the streets for slave labour. Beatings and killings became commonplace. Although approximately 2,000 Jews had managed to escape from the town to the Soviet-occupied zone in the initial days of the occupation, throughout 1939 - 40 the population was swollen by Jews from neighbouring towns and other places in Poland, including Warsaw, Lodz, Belchatow, Kalisz, Gniezno, and Plock.

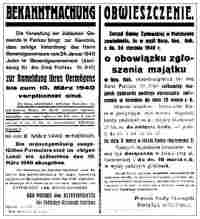

Headed by Zalmen Tenenbaum, a former Vice-President of the pre-war Jewish Council, a 24 member Judenrat was established in the early days of the occupation. Tenenbaum was also appointed President of all of the Judenräte of the county of Piotrkow. In October 1939, the Wehrmacht transferred the administration of the city to the civilian authorities under the command of Oberbürgermeister Hans Drexel, who on 8 October 1939 issued a decree establishing a ghetto, the first in occupied Poland. As elsewhere, living conditions in the ghetto were appalling. 5,000 - 6,000 people had lived in the ghetto area before the war; now 28,000 were incarcerated there. Many houses had no electricity, water supply or basic facilities. The ghetto was closed on 28 October.

Hanka Ziegler was 9 years old when the war began. Her parents and their 5 children lived in Lodz, but moved to Piotrkow in the early days of the war. She recalled:

"We all stayed in one little room, the seven of us. Another 14 people came to the room at different times…I remember sleeping on a chair with one of my brothers, it was awful. My father got caught foraging for food and was put in prison. I never saw my father again…

My brother Zigmund and I were the breadwinners. He was about 14. We collected all the food. He and I started selling bread and potatoes. We didn't have anything else to sell. And then we started scavenging and begging from non-Jewish people. Being such small children we could get through any hole. We learned how to steal, how to beg. My mother was unable to do anything. She just couldn't cope. We were very hungry. So we went out of the ghetto. We went backwards and forwards. Then the day came when they sealed the ghetto..."

Many of the Jews were employed at the Hortensja Glassworks, which mainly produced jars and bottles, at the Kara factory, which manufactured plate glass, or the Bugaj Wood Factory.

Another survivor, Ben Helfgott:

"Young people suffered. From fifteen onwards, they could not walk in the streets for fear of being taken for forced labour. In mid-1940, 200 - 250 were rounded up and taken to build fortifications on the River Bug... There was no real rule that anyone that went out of the ghetto would be shot. Some would be shot, some would be beaten…Our nights weren't safe either. The police would knock on the doors at night to round up young people to be taken away for forced labour."

|

| Decree |

In July 1940, Jews were taken from Piotrkow to two nearby swamps, where they were forced to dig ditches and canals. They were forced to work naked, standing in water up to their waists. Many died of tuberculosis or pneumonia. Some were only 12 years old.

Between June and July 1941, the Germans uncovered the existence of a Jewish underground movement in the ghetto. 11 members of the Judenrat, which had been co-operating with the underground were arrested, including the President, Zalmen Tenenbaum. After more than two months of interrogation and torture, all of the arrested were sent to Auschwitz on 13 September 1941. A few days later, the family of the deportees were informed of their deaths "due to illness". Szymon Warszawski was appointed as the new head of the Judenrat.

Rumours concerning the fate of the Jews of Eastern Europe circulated within the ghetto. Charles Kotkowsky, marching daily to the Hortensja Glassworks, was befriended by a guard, Waclaw Bordo, who one day in spring 1942 passed to him a copy of the underground socialist newspaper Robotnik (Worker). In it, Kotkowsky read of the deportation of the Jews of Lublin to an unknown destination, and of massacres of Jews at Vilna and Slonim. Soon after, Kotkowsky learned of the death camps at Chelmno and Treblinka from other underground newspapers. He told everybody he trusted that the ghettos were being emptied and the Jews gassed. People did not and could not believe it. It was incomprehensible.

|

| German Police in Piotrkow |

"A general curfew was declared, and we knew that the ghetto was going to be deported. An announcement was made that all those who worked in factories outside the ghetto including Hortensja should leave their homes and meet outside the synagogue. I refused to leave my family, but my mother told me to go. I still refused, and then she physically pushed me out of the house. Her last words to me were,'At least let one of our family survive'... That was the last I ever saw of my mother, father and sister."

Jehoszua Cygelfarb (Joshua Segal) had been working in the Hortensja factory for three years. He recalled:

"Everyone had to gather in the square. An SS-officer ordered everybody to stand up, and all those who were working in some capacity were to stand to one side. My brother and I moved to where the officer indicated…An officer moved down the line and selected people to move to the left or right. Fathers and people who had work cards with Swastika approval went to the right, the rest of the families went to the left. When he came to my family, he separated my father from my mother and sisters, but my father refused to leave the family and said, 'I go with my wife', and proceeded to go left.

After the German officer had finished dividing the people, the soldiers surrounded the group and marched them away to the railway station and loaded them into cattle cars without food or water. They were told they were going to a labour camp. The train started down the tracks, going past the glass factory where I was working. I heard the train whistle, and knew without looking up from my lathe what was in that train. But I did not know that my own family were in the boxcars, and that I would never see them again…I was fifteen years old and my brother was nineteen and we were alone."

Artek (Arthur) Poznanski was not yet 15 at the time of the deportations. His brother Jerzyk (Jerzy) was 12. Both worked in the Hortensja factory. On returning to the two and a half streets that now comprised the ghetto, he was handed a note hastily scribbled by his mother:

"We are being taken. May God help you, as we cannot do anything more for you. And whatever may happen, look after Jerzyk. He is but a child and has got no one else." He was distraught. "No parents, no home, no money and a younger brother to look after; what am I going to do?"

Sevek Finkelstein was only 10 years old in October 1942. His mother was selected for deportation, but one of his sisters, Frania, was told by a German officer not to attempt to join her. "Stay where you are", the German said. "Your mother is old, it is all right for her to die, and you are young." Sevek remembered:

"…The people were forced into cattle cars, as many as 150 to one car. Before they were driven into these cars they had to abandon all their possessions. The people were packed into these railroad cars like sardines. Many of the children were crushed to death before the train even left."

Officially there were 2,000 "legal" Jews remaining in Piotrkow, housed in the so-called "small ghetto" on Staro-Warszwska Street. In fact, there were a similar number of "illegal" Jews who had hidden at the time of the deportations and who now mingled with the "legals". The "illegals" led a precarious existence. They were unable to register for legitimate employment, could not obtain ration cards and were constantly seeking shelter. Moreover, the Germans were aware of their existence, and systematically searched for them. Those discovered were gathered in the synagogue then sent to Tomaszow Mazowiecki, from where they were deported to Treblinka together with the Jews of Tomaszow on 3 November. Thereafter, any Jews found hiding in the ghetto were killed where they were found.

Having first worked in the Hortensja and Kara factories, Artek Poznanski was employed by the Befehlsstelle, a Special Orders Group, mainly utilised for the clearing of houses in the former ghetto and the sorting of goods and possessions left behind by the deported Jews. He recalled:

"Disposing of the last traces of many thousands of families (who we suspected, though we were not really sure and refused to credit, were no longer alive) was a heartbreaking operation, but the ever-present threat to our lives hardened us against sentimentality. Every day countless books, diaries, photographs, letters and mementoes of a whole community were thrown on bonfires, while we sorted out mountains of bedding, clothing, furniture, utensils, tools and ornaments, and loaded them on lorries for transport to Germany."

|

| Old Jew in Piotrkow |

|

| Piotrkow Jews |

"In freezing conditions terrorised by bayonets and rifle butts, they were forced to undress, were machine-gunned, and then buried in the trenches. In the confusion of the massacre, six or seven individuals, some wounded, managed to escape. Some time later I met one of them in the Bugaj timberworks, a pale, blue-eyed boy 14 or 15 years old. He told me how, only slightly wounded, he managed to manoeuvre himself on top of a pile of bleeding corpses. Covered with heaps of leaves and chunks of frozen earth, and barely able to breathe, he remained virtually motionless until nightfall. Then under cover of darkness, he crawled out and dragged himself back to the ghetto…I noticed him mainly because of one unusual feature; his hair was completely white."

Five months after the mass deportations, on 21 March 1943, a date chosen to coincide with the Jewish festival of Purim, "legal" Jews were told that there was to be an exchange with German citizens living in the settlement of Sarona, in Palestine. Ten university graduates were required for the exchange, but only eight could be found. They were driven to the Jewish cemetery, where a pit had been dug. There, together with the Jewish watchman of the cemetery and his wife, they were shot.

At the end of July 1943 the small ghetto was liquidated. 1,720 Jews were allowed to remain in Piotrkow – 1,000 in the Bugaj factory and the remainder in the two glassworks. 1,500 other Jews were deported to the forced labour camps at Blizyn, Pionki and Starachowice. On 24 November 1944, the last Jews of Piotrkow were deported to a number of different concentration camps: Buchenwald, Bergen-Belsen, Mauthausen, Ravensbrück and Auschwitz, amongst others.

Piotrkow was liberated by the Red Army on 16 January 1945. Out of the estimated 28,000 Jews who had been imprisoned in the ghetto, 1,600-1,700 had survived, either in the camps or in hiding. Some survivors returned to Piotrkow at the war's end, among them Ben Helfgott. He was not welcomed. He and his cousin, Gienek Klein, were arrested by Polish policemen, who threatened to shoot them. After a desperate appeal, they were released. One of the policemen said, "You can consider yourselves very lucky. We have killed many of your kind. You are the first ones we have left alive." Others were not so fortunate. A Jewish woman, Sala Uszerowicz, had sold her father's apartment in Piotrkow to a Pole for 600 zlotys, the equivalent to about 5 US dollars. She was murdered the same day, together with her fiancée, Lajzer Malc and a friend, Rachel Rolnik.

In 1996, Ben Helfgott returned once more to Piotrkow, this time with Sir Martin Gilbert and a party of English students. At the Hortensja Glass Works they found the register of factory workers from 1940 to 1944. Helfgott's name was listed, together with his address, date of birth and the description Zyd (Jew).

Sources:

Gutman, Israel, ed. Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, Macmillan Publishing Company, New York, 1990

Gilbert, Martin. The Holocaust – The Jewish Tragedy, William Collins Sons & Co. Limited, London, 1986

Gilbert, Martin. Holocaust Journey – Travelling in Search of the Past, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1997

Gilbert, Martin. The Boys – Triumph over Adversity, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1996

Gill, Anton. The Journey Back from Hell – Conversations with Concentration Camp Survivors, Grafton Books, London, 1989

Trunk, Isaiah. Judenrat – The Jewish Councils in Eastern Europe under Nazi Occupation, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 1996

|

| 28,000 Jews lived in the ghetto |

© ARC 2005